Recall that the Employee base class defined a method named GiveBonus(), which was originally implemented as follows:

public partial class Employee { public void GiveBonus(float amount) { currPay += amount; } ... }

Because this method has been defined with the public keyword, you can now give bonuses to salespeople and managers (as well as part-time salespeople):

static void Main(string[] args) { Console.WriteLine("***** The Employee Class Hierarchy *****\n"); // Give each employee a bonus? Manager chucky = new Manager("Chucky", 50, 92, 100000, "333-23-2322", 9000); chucky.GiveBonus(300); chucky.DisplayStats(); Console.WriteLine(); SalesPerson fran = new SalesPerson("Fran", 43, 93, 3000, "932-32-3232", 31); fran.GiveBonus(200); fran.DisplayStats(); Console.ReadLine(); }

The problem with the current design is that the publicly inherited GiveBonus() method operates identically for all subclasses. Ideally, the bonus of a salesperson or part-time salesperson should take into account the number of sales. Perhaps managers should gain additional stock options in conjunction with a monetary bump in salary. Given this, you are suddenly faced with an interesting question: “How can related types respond differently to the same request?” Again, glad you asked!

Polymorphism provides a way for a subclass to define its own version of a method defined by its base class, using the process termed method overriding. To retrofit your current design, you need to understand the meaning of the virtual and override keywords. If a base class wishes to define a method that may be (but does not have to be) overridden by a subclass, it must mark the method with the virtual keyword:

partial class Employee { // This method can now be 'overridden' by a derived class. public virtual void GiveBonus(float amount) { currPay += amount; } ... }

Note Methods that have been marked with the virtual keyword are (not surprisingly) termed virtual methods.

When a subclass wishes to change the implementation details of a virtual method, it does so using the override keyword. For example, the SalesPerson and Manager could override GiveBonus() as follows (assume that PTSalesPerson will not override GiveBonus() and therefore simply inherits the version defined by SalesPerson):

class SalesPerson : Employee { ... // A salesperson's bonus is influenced by the number of sales. public override void GiveBonus(float amount) { int salesBonus = 0; if (numberOfSales >= 0 && numberOfSales <= 100) salesBonus = 10; else { if (numberOfSales >= 101 && numberOfSales <= 200) salesBonus = 15; else salesBonus = 20; } base.GiveBonus(amount * salesBonus); } } class Manager : Employee { ... public override void GiveBonus(float amount) { base.GiveBonus(amount); Random r = new Random(); numberOfOptions += r.Next(500); } }

Notice how each overridden method is free to leverage the default behavior using the base keyword. In this way, you have no need to completely reimplement the logic behind GiveBonus(), but can reuse (and possibly extend) the default behavior of the parent class.

Also assume that the current DisplayStats() method of the Employee class has been declared virtually. By doing so, each subclass can override this method to account for displaying the number of sales (for salespeople) and current stock options (for managers). For example, consider the Manager’s version of the DisplayStats() method (the SalesPerson class would implement DisplayStats() in a similar manner to show the number of sales):

public override void DisplayStats() { base.DisplayStats(); Console.WriteLine("Number of Stock Options: {0}", StockOptions); }

Now that each subclass can interpret what these virtual methods means to itself, each object instance behaves as a more independent entity:

static void Main(string[] args) { Console.WriteLine("***** The Employee Class Hierarchy *****\n"); // A better bonus system! Manager chucky = new Manager("Chucky", 50, 92, 100000, "333-23-2322", 9000); chucky.GiveBonus(300); chucky.DisplayStats(); Console.WriteLine(); SalesPerson fran = new SalesPerson("Fran", 43, 93, 3000, "932-32-3232", 31); fran.GiveBonus(200); fran.DisplayStats(); Console.ReadLine(); }

The following output shows a possible test run of your application thus far:

***** The Employee Class Hierarchy ***** Name: Chucky ID: 92 Age: 50 Pay: 100300 SSN: 333-23-2322 Number of Stock Options: 9337 Name: Fran ID: 93 Age: 43 Pay: 5000 SSN: 932-32-3232 Number of Sales: 31

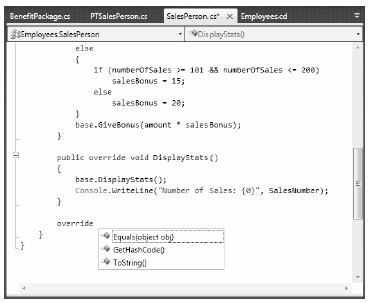

"As you may have already noticed, when you are overriding a member, you must recall the type of each and every parameter—not to mention the method name and parameter passing conventions (ref, out and params). Visual Studio 2010 has a very helpful feature that you can make use of when overriding a virtual member. If you type the word “override” within the scope of a class type (then hit the spacebar), IntelliSense will automatically display a list of all the overridable members defined in your parent classes, as you see in Figure 6-6.

Figure 6-6. Quickly viewing overridable methods à la Visual Studio 2010

When you select a member and hit the Enter key, the IDE responds by automatically filling in the method stub on your behalf. Note that you also receive a code statement that calls your parent’s version of the virtual member (you are free to delete this line if it is not required). For example, if you used this technique when overriding the DisplayStats() method, you might find the following autogenerated code:

public override void DisplayStats() { base.DisplayStats(); }

Recall that the sealed keyword can be applied to a class type to prevent other types from extending its behavior via inheritance. As you may remember, you sealed PTSalesPerson as you assumed it made no sense for other developers to extend this line of inheritance any further.

On a related note, sometimes you may not wish to seal an entire class, but simply want to prevent derived types from overriding particular virtual methods. For example, assume you do not want parttime salespeople to obtain customized bonuses. To prevent the PTSalesPerson class from overriding the virtual GiveBonus() method, you could effectively seal this method in the SalesPerson class as follows:

// SalesPerson has sealed the GiveBonus() method! class SalesPerson : Employee { ... public override sealed void GiveBonus(float amount) { ... } }

Here, SalesPerson has indeed overridden the virtual GiveBonus() method defined in the Employee class; however, it has explicitly marked it as sealed. Thus, if you attempted to override this method in the PTSalesPerson class you receive compile-time errors, as shown in the following code:

sealed class PTSalesPerson : SalesPerson { public PTSalesPerson(string fullName, int age, int empID, float currPay, string ssn, int numbOfSales) :base (fullName, age, empID, currPay, ssn, numbOfSales) { } // Compiler error! Can't override this method // in the PTSalesPerson class, as it was sealed. public override void GiveBonus(float amount) { } }

Currently, the Employee base class has been designed to supply various data members for its descendents, as well as supply two virtual methods (GiveBonus() and DisplayStats()) that may be overridden by a given descendent. While this is all well and good, there is a rather odd byproduct of the current design; you can directly create instances of the Employee base class:

// What exactly does this mean? Employee X = new Employee();

In this example, the only real purpose of the Employee base class is to define common members for all subclasses. In all likelihood, you did not intend anyone to create a direct instance of this class, reason being that the Employee type itself is too general of a concept. For example, if I were to walk up to you and say, “I’m an employee!” I would bet your very first question to me would be, “What kind of employee are you?” Are you a consultant, trainer, admin assistant, copyeditor, or White House aide?

Given that many base classes tend to be rather nebulous entities, a far better design for this example is to prevent the ability to directly create a new Employee object in code. In C#, you can enforce this programmatically by using the abstract keyword in the class definition, thus creating an abstract base class:

// Update the Employee class as abstract // to prevent direct instantiation. abstract partial class Employee { ... }

With this, if you now attempt to create an instance of the Employee class, you are issued a compiletime error:

// Error! Cannot create an instance of an abstract class! Employee X = new Employee();

At first glance it might seem very strange to define a class that you cannot directly create. Recall however that base classes (abstract or not) are very useful, in that they contain all of the common data and functionality of derived types. Using this form of abstraction, we are able to model that the “idea” of an employee is completely valid; it is just not a concrete entity. Also understand that although we cannot directly create an abstract class, it is still assembled in memory when derived classes are created. Thus, it is perfectly fine (and common) for abstract classes to define any number of constructors that are called indirectly when derived classes are allocated.

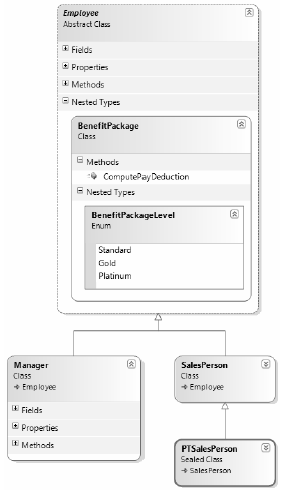

At this point, you have constructed a fairly interesting employee hierarchy. You will add a bit more functionality to this application later in this chapter when examining C# casting rules. Until then, Figure 6-7 illustrates the core design of your current types.

When a class has been defined as an abstract base class (via the abstract keyword), it may define any number of abstract members. Abstract members can be used whenever you wish to define a member that does not supply a default implementation, but must be accounted for by each derived class. By doing so, you enforce a polymorphic interface on each descendent, leaving them to contend with the task of providing the details behind your abstract methods.

Simply put, an abstract base class’s polymorphic interface simply refers to its set of virtual and abstract methods. This is much more interesting than first meets the eye, as this trait of OOP allows you to build easily extendable and flexible software applications. To illustrate, you will be implementing (and slightly modifying) the hierarchy of shapes briefly examined in Chapter 5 during the overview of the pillars of OOP. To begin, create a new C# Console Application project named Shapes.

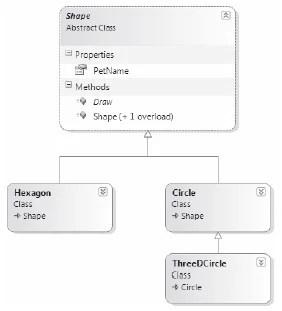

In Figure 6-8, notice that the Hexagon and Circle types each extend the Shape base class. Like any base class, Shape defines a number of members (a PetName property and Draw() method in this case) that are common to all descendents.

Figure6-8. The shapes hieararchy

Much like the employee hierarchy, you should be able to tell that you don’t want to allow the object user to create an instance of Shape directly, as it is too abstract of a concept. Again, to prevent the direct creation of the Shape type, you could define it as an abstract class. As well, given that you wish the derived types to respond uniquely to the Draw() method, let’s mark it as virtual and define a default implementation:

// The abstract base class of the hierarchy. abstract class Shape { public Shape(string name = "NoName") { PetName = name; } public string PetName { get; set; } // A single virtual method. public virtual void Draw() { Console.WriteLine("Inside Shape.Draw()"); } }

Notice that the virtual Draw() method provides a default implementation that simply prints out a message that informs you that you are calling the Draw() method within the Shape base class. Now recall that when a method is marked with the virtual keyword, the method provides a default implementation that all derived types automatically inherit. If a child class so chooses, it may override the method but does not have to. Given this, consider the following implementation of the Circle and Hexagon types:

// Circle DOES NOT override Draw(). class Circle : Shape { public Circle() {} public Circle(string name) : base(name){} } // Hexagon DOES override Draw(). class Hexagon : Shape { public Hexagon() {} public Hexagon(string name) : base(name){} public override void Draw() { Console.WriteLine("Drawing {0} the Hexagon", PetName); } }

The usefulness of abstract methods becomes crystal clear when you once again remember that subclasses are never required to override virtual methods (as in the case of Circle). Therefore, if you create an instance of the Hexagon and Circle types, you’d find that the Hexagon understands how to “draw” itself correctly or at least print out an appropriate message to the console. The Circle, however, is more than a bit confused:

static void Main(string[] args) { Console.WriteLine("***** Fun with Polymorphism *****\n"); Hexagon hex = new Hexagon("Beth"); hex.Draw(); Circle cir = new Circle("Cindy"); // Calls base class implementation! cir.Draw(); Console.ReadLine(); }

Now consider the following output of the previous Main() method:

***** Fun with Polymorphism ***** Drawing Beth the Hexagon Inside Shape.Draw()

Clearly, this is not a very intelligent design for the current hierarchy. To force each child class to override the Draw() method, you can define Draw() as an abstract method of the Shape class, which by definition means you provide no default implementation whatsoever. To mark a method as abstract in C#, you use the abstract keyword. Notice that abstract members do not provide any implementation whatsoever:

abstract class Shape { // Force all child classes to define how to be rendered. public abstract void Draw(); ... }

Note Abstract methods can only be defined in abstract classes. If you attempt to do otherwise, you will be issued a compiler error.

Methods marked with abstract are pure protocol. They simply define the name, return type (if any), and parameter set (if required). Here, the abstract Shape class informs the derived types “I have a method named Draw() that takes no arguments and returns nothing. If you derive from me, you figure out the details.”

Given this, you are now obligated to override the Draw() method in the Circle class. If you do not, Circle is also assumed to be a noncreatable abstract type that must be adorned with the abstract keyword (which is obviously not very useful in this example). Here is the code update:

// If we did not implement the abstract Draw() method, Circle would also be // considered abstract, and would have to be marked abstract! class Circle : Shape { public Circle() {} public Circle(string name) : base(name) {} public override void Draw() { Console.WriteLine("Drawing {0} the Circle", PetName); } }

The short answer is that you can now make the assumption that anything deriving from Shape does indeed have a unique version of the Draw() method. To illustrate the full story of polymorphism, consider the following code:

static void Main(string[] args) { Console.WriteLine("***** Fun with Polymorphism *****\n"); // Make an array of Shape-compatible objects. Shape[] myShapes = {new Hexagon(), new Circle(), new Hexagon("Mick"), new Circle("Beth"), new Hexagon("Linda")}; // Loop over each item and interact with the // polymorphic interface. foreach (Shape s in myShapes) { s.Draw(); } Console.ReadLine(); }

Here is the output from the modified Main() method:

***** Fun with Polymorphism ***** Drawing NoName the Hexagon Drawing NoName the Circle Drawing Mick the Hexagon Drawing Beth the Circle Drawing Linda the Hexagon

This Main() method illustrates polymorphism at its finest. Although it is not possible to directly create an instance of an abstract base class (the Shape), you are able to freely store references to any subclass with an abstract base variable. Therefore, when you are creating an array of Shapes, the array can hold any object deriving from the Shape base class (if you attempt to place Shape-incompatible objects into the array, you receive a compiler error).

Given that all items in the myShapes array do indeed derive from Shape, you know they all support the same "polymorphic interface" (or said more plainly, they all have a Draw() method). As you iterate over the array of Shape references, it is at runtime that the underlying type is determined. At this point, the correct version of the Draw() method is invoked in memory.

This technique also makes it very simple to safely extend the current hierarchy. For example, assume you derived more classes from the abstract Shape base class (Triangle, Square, etc.). Due to the polymorphic interface, the code within your foreach loop would not have to change in the slightest as the compiler enforces that only Shape-compatible types are placed within the myShapes array.

C# provides a facility that is the logical opposite of method overriding termed shadowing. Formally speaking, if a derived class defines a member that is identical to a member defined in a base class, the derived class has shadowed the parent’s version. In the real world, the possibility of this occurring is the greatest when you are subclassing from a class you (or your team) did not create yourselves (for example, if you purchase a third-party .NET software package).

For the sake of illustration, assume you receive a class named ThreeDCircle from a coworker (or classmate) that defines a subroutine named Draw() taking no arguments:

class ThreeDCircle { public void Draw() { Console.WriteLine("Drawing a 3D Circle"); } }

You figure that a ThreeDCircle “is-a” Circle, so you derive from your existing Circle type:

class ThreeDCircle : Circle { public void Draw() { Console.WriteLine("Drawing a 3D Circle"); } }

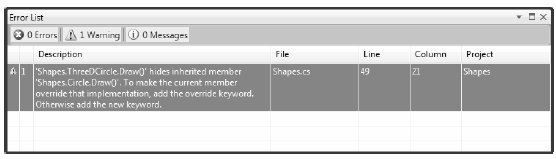

Once you recompile, you find a warning in the Visual Studio 2010 error window (see Figure 6-9).

Figure 6-9. Oops! You just shadowed a member in your parent class

The problem is that you have a derived class (ThreeDCircle) which contains a method that is identical to an inherited method. Again, the exact warning reported by the compiler is:

'Shapes.ThreeDCircle.Draw()' hides inherited member 'Shapes.Circle.Draw()'. To make the current member override that implementation, add the override keyword. Otherwise add the new keyword.

To address this issue, you have two options. You could simply update the parent’s version of Draw()using the override keyword (as suggested by the compiler). With this approach, the ThreeDCircle type is able to extend the parent’s default behavior as required. However, if you don’t have access to the code defining the base class (again, as would be the case in many third-party libraries), you would be unable to modify the Draw()method as a virtual member, as you don’t have access to the code file!

As an alternative, you can include the new keyword to the offending Draw() member of the derived type (ThreeDCircle in this example). Doing so explicitly states that the derived type’s implementation is intentionally designed to effectively ignore the parent’s version (again, in the real world, this can be helpful if external .NET software somehow conflicts with your current software).

// This class extends Circle and hides the inherited Draw() method. class ThreeDCircle : Circle { // Hide any Draw() implementation above me. public new void Draw() { Console.WriteLine("Drawing a 3D Circle"); } }

You can also apply the new keyword to any member type inherited from a base class (field, constant, static member, or property). As a further example, assume that ThreeDCircle wishes to hide the inherited PetName property:

class ThreeDCircle : Circle { // Hide the PetName property above me. public new string PetName { get; set; } // Hide any Draw() implementation above me. public new void Draw() { Console.WriteLine("Drawing a 3D Circle"); } }

Finally, be aware that it is still possible to trigger the base class implementation of a shadowed member using an explicit cast, as described in the next section. For example, the following code shows:

static void Main(string[] args) { ... // This calls the Draw() method of the ThreeDCircle. ThreeDCircle o = new ThreeDCircle(); o.Draw(); // This calls the Draw() method of the parent! ((Circle)o).Draw(); Console.ReadLine(); }

Source Code The Shapes project can be found under the Chapter 6 subdirectory.